With the advent of the British regime, the rules of the fur trade game changed. But there was more to come.

Under the Treaty of Paris, signed in 1783, Great Britain had been forced to recognize the independence of the United States. As new borders were set, the English and Scottish traders of Montréal were shut out of the market for furs from the Great Lakes and Illinois.

In response, they founded the North West Company and turned to the Far North, determined to challenge the all-powerful Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) on its own territory. Lachine became their base of operations. It was in this context that, in 1803, Alexander Gordon had a stone warehouse built to store furs and trading goods for the so-called Nor’Westers.

Competition between the two companies was fierce, especially after British settlers supported by HBC founded a colony on the Red River. While the humans clashed, the animals were being critically over-hunted, and revenues began to decline.

Hudson’s Bay Company and the little emperor

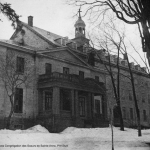

Finally, in 1821, the British authorities forced the rival companies to merge under the name Hudson’s Bay Company and appointed a new governor, George Simpson. He was small of stature but vigorous and, above all, autocratic, hence his nickname “Little Emperor.” Simpson decided to administer all corporate operations from Montréal Island and made Lachine his headquarters.

His death, in 1860, marked the end of the fur-trade reign that had begun with the brother-in-law associates Charles Le Moyne and Jacques Le Ber. But in 1861, when the Sisters of Saint Anne purchased Simpson’s manor to establish a boarding school and a public school, they were beginning a new era, that of universally accessible education, in particular for girls.